Navigating the Reading Wars With English Learners

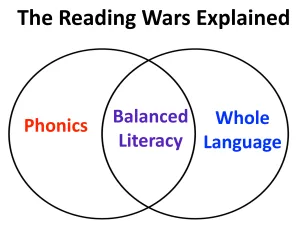

If you follow literacy issues, you have probably heard of the Reading Wars. If you haven’t, Jill Barshay’s recent article for the Hechinger Report does the best job I’ve seen yet of explaining the nuts and bolts of this disagreement over how to best teach young children to read. As comprehensive as the story was, however, it failed to mention English learners (ELs). This is disappointing but not unique. ELs often suffer collateral damage in the Reading Wars because both sides overlook their specific needs. Let’s address this issue from an EL’s perspective.

One Side – Phonics

People on this side feel phonics has been neglected. They maintain children need explicit, systematic instruction to learn to easily decode words. Everyone seems to agree this is important; the difference lies in how much emphasis people think it should get. Strong proponents of this approach have even lobbied state legislatures to mandate “science of reading” training for elementary teachers. My state of North Carolina recently joined at least 20 other states that have done or are considering doing this. I think teaching children to fluently decode words is a necessary first step in learning to read. I just have doubts about state legislators determining curriculum at such a nuts-and-bolts level. Local education experts are best placed to make these decisions. Phonics has gotten a bad reputation from dreary worksheets and inauthentic language, like these examples from decodable readers:

- “The ham is in the cab.”

- “The hen is in the den.”

- “I hug my pug on the bus.”

As a teacher, I was trying to help ELs understand low utility words like cot or den. Instead, the first word newcomers invariably wanted to know how to read and write was cousin. It wasn’t decodable, but it was a high-utility word for them because they needed it to describe their large extended families. A second grade EL once told me he didn’t truly understand what a dam was until his class studied landforms in science. That’s probably because his exposure to dam during his phonics lessons in kindergarten and first grade was devoid of meaning.

The Other Side – Whole Language

This approach relies on students memorizing sight words and using context and picture clues to figure out unknown words. A familiar feature of this method is predictable texts, the kind where students read sentences like “I have a dog,” and a picture of a dog is next to the text. This isn’t reading by sounding out the words; it’s “reading” using oral language and picture clues. A teaching colleague once asked me to teach a newcomer EL the meaning of t-shirt. Apparently, the newcomer hadn’t done well on an assessment that required her to read predictable text that said, “I have a t-shirt.” The newcomer couldn’t read the page, but it was because she didn’t have the oral vocabulary needed to identify t-shirt. In this case, context clues from pictures didn’t help the newcomer. It didn’t give the teacher an accurate assessment of her reading, either. This hurts ELs.

Meeting in the Middle

Many school systems attempt to please both sides of the Reading Wars with an approach called balanced literacy. Critics feel this doesn’t give enough attention to the systematic teaching of phonics. A key feature of the balanced literacy method is guided reading groups, where the teacher uses leveled texts with small groups of students at a similar reading level. ELs often end up in low-level groups, missing chances to be exposed to grade-level text. When teachers spend a big part of the literacy block working with guided reading groups, it means most students are not with the teacher. Some “keep busy” activities (computer games, worksheets, etc.) that students are doing instead often don’t benefit ELs much.

Tips

All three approaches I’ve described have pitfalls for ELs. You may not be able to decide which side of the Reading Wars your district takes, but as a teacher of ELs, you can and should be an influencer. Work to ensure your students don’t become collateral damage in these conflicts. Here’s what to do:

- Encourage meaning-first instruction. Any method of teaching reading will fail ELs if they don’t understand the vocabulary. That means ELs need to understand what a cot is as they’re also learning to sound out the word.

- Ensure ELs are doing pair and group work in mixed-level groups. This gives them exposure to a wide variety of speaking opportunities and reading materials.

- Don’t give short shrift to science and social studies. These subjects offer valuable opportunities to work with grade-level text.

- Explore thematic instruction in the literacy block to build background knowledge. Decoding, increasing fluency, and finding the main idea are important, but they’re only mile markers on the road to reading. The end point of any instructional approach is for students to learn things from their reading. Building background knowledge helps.

Do you know what approach to the Reading Wars your district takes? What about you? How have you ensured your students don’t get caught in the middle?

About the author

Barbara Gottschalk

Barbara Gottschalk is a veteran educator. She has taught English language learners from first graders to graduate students in five states in three very different parts of the United States plus Japan. Gottschalk has written many successful grants and served as a grant reviewer for TESOL, the National Education Association, and the U.S. Department of Education's Office of English Language Acquisition. She is the author of "Get Money for Your Classroom: Easy Grant Writing Ideas That Work" and "Dispelling Misconceptions About English Language Learners: Research-Based Ways to Improve Instruction."