Assessing Assessments: 5 Points to Consider

Are you preparing to begin a new academic year? For many teachers in the United States and other parts of the world, the answer is “yes.” Even if this isn’t the case for you, it’s safe to assume almost every teacher of English learners (ELs) will be welcoming both new and returning students back to regular classes after the pandemic.

One of the first things teachers will want to determine is their students’ baseline reading ability. This is good—but it’s also fraught with pitfalls for ELs. Many reasons explain why ELs’ reading ability might not be accurately assessed. These considerations don’t excuse performance relative to non-ELs but instead contextualize it.

1. What Is the Assessment Really Testing?

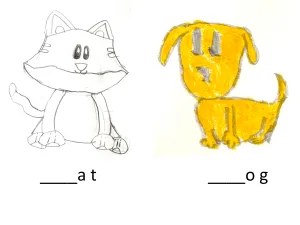

Watch out for assessments that aren’t really testing reading ability. The following example asked first graders to write the initial consonant for each word:

Pictures are a great way to teach initial sounds, but an assessment like this assumes too much. If ELs don’t know the word for cat or dog in English, they won’t be able to supply the initial consonant in English. A teacher who uses an assessment like this one might conclude a student didn’t know initial sounds when instead, the student didn’t know the names for the pictures. The test was assessing the wrong thing.

Another common miscalculation with assessments involves assuming students don’t understand what they’ve read if they can’t talk or write about it, forgetting receptive domains like reading can develop faster than productive domains. I’ve had perceptive, more proficient ELs tell me, “I know what this means, but I just can’t say it.” I believed them. You should too.

2. Did the Students Understand Testing Protocols?

I’ve learned students can sometimes misunderstand questions even on a language-free assessment, so this might not tell you everything your students know. Even simple formative classroom assessments are subject to measurement error if students don’t understand directions. For example, an observant staff member at my school told me she realized while she was asking first graders to tell her the first sound in a word that students didn’t understand what first and last meant. Results from this kind of evaluation would indicate students don’t know their sounds. In fact, they couldn’t demonstrate their knowledge because they didn’t understand the assessment directions.

3. Is There Cultural Bias in the Assessment?

Newcomers may have little background knowledge of common school activities, such as field trips and seasonal activities. Reading passages about these unfamiliar topics will not accurately assess ELs’ reading ability. In the United States, each state’s annual test of English language proficiency (for example, WIDA ACCESS, KELPA) is likely one of the few assessments ELs take that has been normed on that population. That’s a good thing. It’s also why teachers should take information from assessments not normed on ELs with a large grain of salt.

4. Is the Assessment Acknowledging All the Student’s Knowledge?

Testing bilingual students in only English ignores the other—possibly large—portion of their knowledge. Reading assessments are likely not available in all of your students’ native languages. Still, if your older ELs have attended school in their home countries, ask them to read you something in their native language. That’s a good reason to have a supply of bilingual books in various languages on hand.

For example, when I asked a fifth-grade newcomer from Vietnam to read a Vietnamese picture book aloud to me, she did so in what sounded to me like fluent Vietnamese. I wasn’t sure because I didn’t know Vietnamese. Still, because it seemed she had reading ability in her native language, I knew she could transfer those reading skills to another language.

5. Will the Assessment Be Used to Gauge Improvement?

Most likely this past year has been fragmented and interrupted with cancelled assessments and absent students. There’s nothing you can do about that now. What you can do, though, is establish a baseline reading ability for your students to help you later determine their improvement.

Often, reading assessments aim to identify specific reading weaknesses so they can be remediated. That’s okay if the student has one, but there’s nothing wrong with most ELs. An EL might, for example, need to work on mastering vowel sounds or understanding the main idea, but even after that, the overall language acquisition process continues. Most ELs don’t need targeted instruction; they’re simply still learning the language. Tracking students’ long-term progress is difficult but necessary if you want to form high, but not hurried, expectations for your ELs’ reading progress.

It’s important to assess your ELs’ reading ability as you begin a new academic year. Don’t discount these assessment results. Instead, explain them and work to improve them in the coming year!