Are Your EL Expectations High—or Hurried?

January brings the beginning of a new year and an opportunity to start fresh. We make resolutions and hold ourselves to high expectations. After a few weeks, however, resolve dwindles. Why? Experts say we need to set achievable goals and hold reasonable expectations for ourselves.

We need to do the same for our English learners (ELs). Slow and steady worked for the turtle in the classic tortoise and hare fable, and it works for reading too. As we begin a new year, let’s take a fresh look at our reading expectations for our ELs. Are we aligning them to our students’ developmental needs as well as to the curriculum? In other words, are we holding students to high expectations or just hurrying them?

Here are some examples of hurried reading expectations and more appropriate alternatives:

| Hurried Expectations | High Expectations and Considerations |

| Why doesn’t this entering kindergarten student know his letters and sounds? | Is this student comfortable coming to school? |

| Why aren’t all of my kindergarten students reading at the end of the year? | Are all of my developmentally ready students reading by the end of kindergarten? |

| She hasn’t progressed this year. | Compile and use longitudinal data to determine this student’s progress for the past 5 years. Students rarely progress on an even upward trend. |

| Feedback to a parent: “He’s not reading at grade level.” | Feedback to a parent: “He’s not reading at grade level, but he came to the United States just 2 years ago. He’s been making steady progress since then and is on track to catch up completely in a few more years.” |

| High school ELs with limited or interrupted formal schooling should graduate in 4 years with their cohort. | Four years isn’t enough. High school ELs with limited or interrupted formal schooling should have the time and supports they need to graduate. High schools shouldn’t be penalized for giving them the time to do so. |

| ELs should be reading at grade level by third grade. | Third-grade ELs have had just 4 years or less of EL instruction, still not long enough, since it takes 5–7 years, on average, to reach proficiency. Third-grade reading laws should allow retention exemptions for all ELs. |

| Beginning level student in a college intensive English program: “I’ll only need one semester of English before beginning regular classes!” | Mastering academic language is more difficult than simply learning social English. It will take more than a few months. |

| This student will never finish our community college’s sequence of English courses. | What is this student’s purpose for learning? Perhaps the student has an intermediate goal, not necessarily obtaining a degree or completing a course of study. |

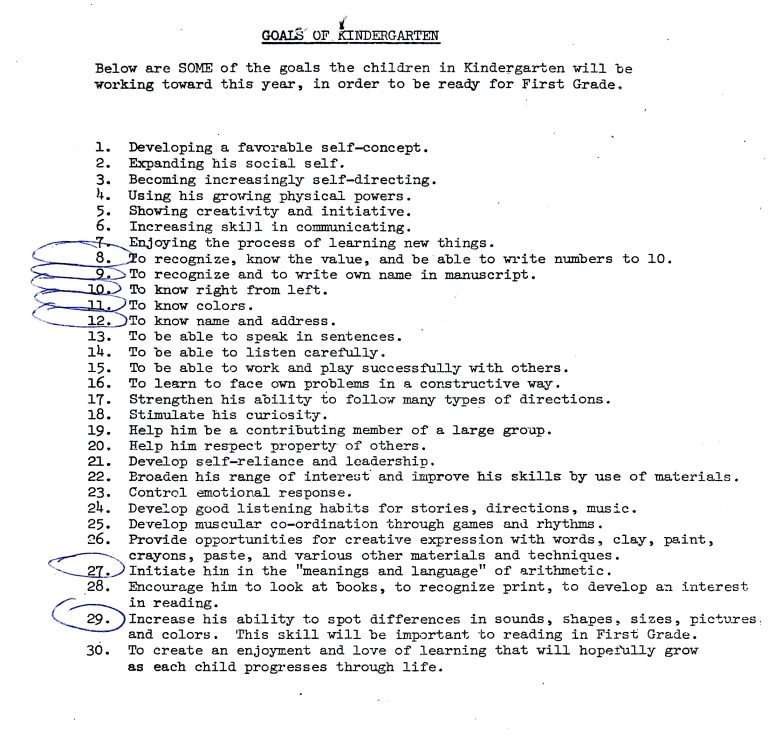

A final example of how high expectations can morph into hurried ones is this “goals of kindergarten” from the 1960s:

It’s telling to compare these goals from nearly 60 years ago to this kindergarten language arts standard typical of many states now: “Read emergent-reader texts with purpose and understanding.” Expectations for kindergarten have changed, but children haven’t. A wise kindergarten teacher once pointed out to me that some of her kindergarten students were ready to learn to read in kindergarten, just not all of them. Holding children to hurried expectations before they may be developmentally ready is akin to thinking children can grow permanent teeth faster if they just try harder and their parents work with them more at home.

One of the hottest must-have kitchen items a few years ago was the Instant Pot. It’s symbolic of many of our hurried expectations. The Instant Pot is a slow cooker, but it’s also a pressure cooker. That’s not what we want for our English learners. They need both patience as well as rigor. They can meet high, realistic expectations with time.

About the author

Barbara Gottschalk

Barbara Gottschalk is a veteran educator. She has taught English language learners from first graders to graduate students in five states in three very different parts of the United States plus Japan. Gottschalk has written many successful grants and served as a grant reviewer for TESOL, the National Education Association, and the U.S. Department of Education's Office of English Language Acquisition. She is the author of "Get Money for Your Classroom: Easy Grant Writing Ideas That Work" and "Dispelling Misconceptions About English Language Learners: Research-Based Ways to Improve Instruction."